So the other week, I go to the doctor’s office with one of my kids for their annual physical. And before the exam, the doctor makes small talk for a while, as he does, to talk about a healthy life and all that. And he asks my kid what he does after school. And my kid, being a normal and honest kid, starts saying stuff like: I like to hang out with my friends and play video games. And then the doctor interrupts him. He leans forward, sticks his finger up in the air, and says: Hold on, you’re going to this amazing high school, with hundreds and hundreds of activities. When colleges look at you, I can guarantee they don’t want to know how much time you spent playing video games or hanging out with your friends.

I was thinking: what is happening here? And I interrupt him back now and say, you know you interrupted him, he wasn’t finished. And my kid, realizing what the man wants to hear, tells his doctor/inquisitor about his more adult-approved, official, you can put them on a college application-someday activities. And the doctor lightens up after this, sends him into the other room to take off some of his clothes, and proceeds to give him his physical, which I guess goes better from there.

But the more I thought about this moment, the more incensed I became. Because I wondered when did every interaction my teenagers have with an adult turn into a precursor for a college acceptance interview, years away from that being an actual possibility? Who decided that this interrogation should be part of the assessment of my child’s health? When did childhood become a race toward the achievement of a goal that somebody else sets for you? A goal that may or may not be part of your best life.

To me, this moment in the doctor’s office for my child was not a weird, outlying experience, but a symptom of the world as it is, but not as it is meant to be. I think all times and places and cultures have their own plusses and minuses. But here in our 21st century, urban, blue state, university-town America, I think we have some of our own frankly weird habits and dysfunctions that choke out the best of what we want in life in general, and maybe in the holiday season in particular.

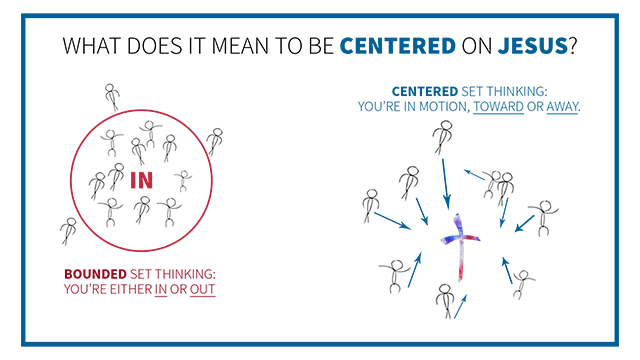

Today of course is the Sunday after Thanksgiving, and it’s also in the church world the first Sunday of the Christmas season called Advent. Advent is a season of remembering the birth of Jesus, and the longings and hopes and expectations associated with his life. And it’s a time to long for Jesus to come again, to be centered more fully both in our lives and in history, and to do God’s good work there.

In this year’s Advent season, we’re thinking about pilgrimage, walks people make, journeys we take, that have something to do with the Christmas story and the movement Jesus provokes.

At its best, the holiday season can be a time for gratitude, wonder, joy, and connection. But to welcome something good, we need to make room for it. So today, on this first week of our Christmas season, I want to take a moment to notice some of the stress and other issues that can choke out our joy, and look at some ways we might need to walk away from things to make room for the gifts of Jesus.

The first of the Bible’s biographies of Jesus opens with a lot of comings and goings, people – including Jesus – on pilgrimage. Let me read you one little bit.

Matthew 2:13-15 (CEB)

13 When the magi had departed, an angel from the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream and said, “Get up. Take the child and his mother and escape to Egypt. Stay there until I tell you, for Herod will soon search for the child in order to kill him.” 14 Joseph got up and, during the night, took the child and his mother to Egypt. 15 He stayed there until Herod died. This fulfilled what the Lord had spoken through the prophet: I have called my son out of Egypt.

This is just a tiny excerpt from Matthew’s account of the first Christmas, which isn’t a winter wonderland, but a tale of international intrigue, violence, and dramatic escape. Here the magi – astrologers from Persia – have just wrapped up their visit to worship the newborn king they thought was born in Bethlehem.

But a messenger tells Joseph he can’t bask in the wonder of that experience. His family needs to flee the country because the big bad king of their nation, the Roman collaborator Herod, doesn’t like hearing rumors of other kinds in his land and is coming after them. From here on out, Matthew turns the Christmas story into a retelling of the Exodus – the founding rescue story of the Jewish people, where Moses leads the people out of slavery in Egypt, barely rescuing them from the violent, maniachal Pharoah.

This time, King Herod plays the part of Pharaoh.

And Jesus plays the part of both the Jewish people and of Moses. First, he and his family have to find refuge in Egypt, as Joseph and his brothers do in a famine in the end of the book of Genesis.

And then, like Moses, Jesus will be called out of Egypt and to the promised land. Off and on throughout Matthew, Jesus will be the new Moses, God’s great leader chosen to teach people how to live and to liberate people, to guide us out of bondage and into freedom.

For people living under profound suffering, Jesus has always been the new Moses, the great hope of liberation. Just as the Exodus is the central backstory for Jewish believers, so has the Exodus and Jesus as the new Moses been central to the theology and hopes and worship of African-American Christianity.

The great American theologian James Cone and others have helped us see again that Jesus was a person of color born under the power of a violent empire and he began his public ministry at age 30 proclaiming freedom for the captives.

Boston’s own theological legend Howard Thurman put it simply, that the good news of Jesus – and in fact all of the Bible – was to people whose backs were against the wall.

We had a little service here Monday evening to remember and voice the ways that some of us have our backs against the wall. We held a service of lament that was planned and led by a number of women in our community. Lament is where we voice our anger and disappointment and frustration to God and ask God: How Long? And demand that God act. This beautiful wooden tree crafted by our own Phil Reavis for the occasion began the evening barren, but it was filled up with these leaves that have some of the laments of our community written on them.

We wrote down our laments of violence, of loss, of injustices big and small, of things personal, things global and political.

Matthew begins his biography with Jesus’ daddy dreaming that Jesus is named Immanuel – God with us. And then when Jesus is a toddler, Joseph finds out they have to flee to Egypt and then come back up from that land, and now to Joseph and all the rest of us, Jesus is our liberator Moses as well.

What that says to us is that God is with us in our suffering and disappointment and anger – that God is with us when we’ve been done wrong, that God is with us as we wait and struggle for justice, that God is with people of the earth – near and far – who are bullied or oppressed or harmed.

This is obviously not a story just about us. When we remember the Christmas story, we’re called to remember and pray for people like my Uyghur friends suffering a kind of genocide. We’re called to remember and pray for and stand with the bullied, the diminished, the hated, the outcast; the people run out of their homes and their homelands and driven out of their minds with hurt.

But I think Jesus the Liberator even speaks to us in our everyday Greater Cambridge lives, even places like my son’s visit in the doctor’s office the other week.

See, I think Jesus is interested in leading people out of all the things – external and internal – that trap us, that crush us, that choke out joy and wonder and connection.

Teens and preteens and kids in the room know like nobody else that when you’re measured and compared by others – when other people use their voice to tell you how you measure up to other kids or their picture of what a successful kid should be like at your age, it’s hard to be happy. It’s hard to have peace and freedom when you’re being judged and evaluated. Actually, a lot of us in this room know about this. Grad students, moms, people with harsh bosses, anybody here who’s been on a dating app this past year – how much freedom do you experience when you’re being subjected to other people’s judgment and evaluation? When you’re being measured by a standard that you didn’t choose and that might not be fair or realistic?

Maybe in this season before Christmas, we need to ask some questions about the exodus that Jesus will lead us on, about what we might need to walk away from, if we’re going to make room for freedom.

With my kid, that hasn’t meant walking away from that doctor and finding a different one, although it could if it had to, I suppose. But it did mean a few different conversations about how that doctor is not the boss of him, how our kid’s doctor doesn’t get to define success for our son. That what college you to go, or whether you ever go to college or not, is not the measure of your worth. It’s not the goal of your childhood.

It’s a weird thing that in our city these days, to tell a teenager you love them and you’re proud of them, regardless of their grades or test scores or resume, that feels like a subversive act. And don’t be fooled, the kids who have all the best of all those things need to hear this liberating truth as much as the kids who don’t.

I’m suggesting today that there might be ways we all need Jesus as a Liberator – I know that I do.

I’ve been in a season of midlife where for months, years really, I’ve been asking what it means to live a less pressurized life, a less stressed-out life, and a life with more room for joy and gratitude and wonder and connection. And as I’ve explored this, I’ve learned that when I settle into the stressed out life, the pressured life, the joyless life, the lonely, disconnected life, I’m getting the results the system we’re living in was designed to create for me.

This past week, we published a Thanksgiving blog I wrote, where I thoughts about some of the roots of our current economy, and some of the havoc our economy and culture wreaks in many of our lives.

And I made up a game I encouraged us to try playing. I called it the Not My Fault Game. Because it’s healthy to take responsibility for our lives. But our economy, our culture, and our inner critics also tend to shame us when we have problems, even when they’re not our fault. And, because shame tends to choke our joy and wonder, and because shame is also often not a really great motivator or change agent, it can be liberating to discover the problems we blame ourselves for that aren’t really our fault.

This game is better when you play it with a friend, but I played it by myself this year. The way it works is you write down five or ten problems that stress you out. I think I had eight. And then next to each problem, you write down if it’s mainly your fault or mainly not your fault. I had four not my faults, three my faults, and one on which I cheated – I thought half and half.

And you know what, there was more that was liberating about this game than I even thought would be.

First off, there was this thing I had forgotten about when I wrote the blog. When you write your problems down, this weird thing happens. You think it’s going to get worse, like writing them down is going to depress you or get you fixated on what’s wrong. But for most of us, the opposite happens. I write down my biggest problems and I’m like: hey, there are only 8. Two pages worth, that’s all. And really, they could be much, much worse.

There’s science behind this, I gather. That externalizing our problems, our stresses, writing them down helps us see their true size and scope, which most of the time, for most of us, is smaller than we think.

Secondly, noticing that many of these problems aren’t primarily my fault is liberating too. It doesn’t take them away, but it does lift shame and it makes room for me to not take them so personally. Like lots of people alive today have these problems because the system we live in is creating them.

And then lastly, there was this way that Jesus seemed to show up for me in the naming of the problems. Whether I wrote “my fault” or “not my fault” next to them; in many cases, certainly in some of the problems that bothered me most, there was the beginnings of a whisper, a nudge, about where to go from here.

It seems like in some cases, there were ways out. Ways to walk away, ways to shift my attention, shift my habits. Because I was noticing the river I’m swimming in – some of the negative forces of our culture’s impact on me, and some of the negative impacts of my own habits and choices on myself as well.

But I felt Jesus with me, reminding me that God is with me, and that Jesus has taught me before how to swim upstream.

So it was liberating to get my problems out of my head, and it was liberating to realize that many of them are not my fault. And it was liberating to see that at least in some cases, with the help of God, and the direction of Jesus, there were ways out.

There’s a religious word for this last kind of liberation, a word that’s often been associated with this first week of advent, and that word is repentance.

Repentance means turning, or changing direction. A psychologist named Dan Allender was doing some teaching about the dynamics of repentance recently, and he says repentance starts in the belly. Repentance is that awareness in our gut of the distance between our current experience and the deep desires of our heart. That sense deep within that the way I’m engaged in the world is not the way I long for, it’s not the way it’s meant to be. Repentance begins when this longing stirs, the longing to live with the freedom and delight of children of the living God.

And for me, that’s where the “Not My Fault” game led – fault or not, there were at least some areas of my life where it stirred a longing for a different way, and an awareness of at least some shifts God could give me power to make that would bring greater freedom, that would lead me away from stress and compulsion and loneliness and misery and open up space for greater joy and wonder and connection.

I’m a little hesitant to use some of the religious tradition’s words for this journey of freedom – words like sin, repentance, or idolatry. But I want to name them so that those of us who come from a religious heritage or that any of us who will read the Bible, for instance, will recognize some of what it’s talking about at its best here.

Because Matthew’s Christmas story of liberation has this in mind as well. For Matthew, Jesus as the new Moses first calls to mind the Exodus, as I said. Jesus is born for those whose backs are against the wall, to accompany those who are bullied or oppressed or victimized or diminished – to give us hope and resources, and love and power and freedom in desperate places. But there’s a second context of liberation that Matthew evokes as well, with this line “I have called my son out of Egypt.”

Because that line is the first verse in the eleventh chapter of a little book of prophecy in the Hebrew scriptures, where the stakes for liberation aren’t crushing, unpaid labor, but idolatry.

Hosea 11 begins,

“When Israel was a child, I loved him. And out of Egypt, I called my son.”

Now I like to remind people when they’re trying make sense of the Bible that there’s a lot of stuff that’s been added in there over the years that doesn’t always serve us. The chapter breaks, the verse numbers, certainly all the little titles and notes and sub-headings – those have all been added by editors over the years, and sometimes they help, sometimes they don’t.

But in this case, the headings the editors put in my Bible, I think, capture the drift of the chapter pretty well. The sub-headings for this chapter are “Divine Love”, “Divine Frustration”, “Divine Compassion”, and people’s collective “Responses.”

Divine love is the starting place. God loves us and made us to live in freedom, with gratitude, with the gift of wonder, with abundant joy and connection.

But there’s a divine frustration that our human systems and cultures and choices tend to trap us, to bind us, to narrow us – to long for certainty and control instead of wonder. To find fault and complaint instead of gratitude. To compound our own and other’s misery and loneliness, rather than welcoming joy and connection. And that’s frustrating for God – not because God’s random or annoying but again, because God loves us.

But divine frustration is born out of and accompanied by divine compassion. Hosea has God saying, “How could I ever give you up? … My heart winces within me… my compassion grows warm and tender.” I see you, I suffer with you, I am so warmed with love and attention when I think of you, are the thoughts of God toward us.

And then we’re invited to respond – to welcome compassion and this kindly disposition and this longing for our freedom, to turn toward the ways for our own and others’ liberation.

Some of the words of passages like this – sin, idolatry, repentance – have admittedly gone south for many of us. These are words and concepts that have become associated with a singularly privatized, very moralistic religious practice. And yet they weren’t meant to be at one time, or they don’t have to be.

At best, these are words that are trying to tell this story of liberation, of freedom. Idolatry has to do with fixing our attention on false promises, on latching on to things that are supposed to help and protect us but don’t. So maybe for our culture, idolatries would include my kids’ doctor’s message to him. That more supposed success always equals more freedom. That attending higher ranked schools, or landing higher paying jobs, or living in wealthier zip codes, or winning status prizes is the ticket to the promised land. When it turns out that more often than not, the chase of those things wears us down, stresses us out, diminishes our happiness and our soul, cuts other people out of the dream – the people we need to beat to get those things, doesn’t in the end deliver on the goods it promised in the first place. We get stress, we get debt, we get loneliness, we sometimes get a smug sense of superiority, but we don’t always get freedom.

Or maybe our idolatries look something like how we’re told a thousand times a day – especially this time of year – that more consumption is going to give us more joy. When consuming more is really going to trash our struggling earth, grow our debts and stress, and transfer our peace of mind and wonder and wealth to other people.

One of the most universally beloved figures of the Jesus-tradition’s history, other than Jesus himself, is Saint Francis of Assisi, that 12th century privileged kid who felt a call to literally sell everything he had and give it away, to rebuild a church, and to kiss lepers, and talk with animals, and write poems and sing songs about God’s love, and make friends with enemies, and try to bring peace in the Middle East.

Last week I reread the poet Abigail Carroll’s collection of letters to Saint Francis, called A Gathering of Larks. She has this poem/letter about freedom that begins Dear Dreamer…

She writes to Francis:

“If we had possessions, we would need weapons and laws to defend them,” you told the bishop, who must have thought you mad to give up armor, clothing, horses, furniture, clocks. But you had a point. Me, I’m not so rich as to need fancy locks, alarms, or — God forbid — a gun to protect my goods. Most all i have is passed down or a thrift-store find. If there’s anything I have a lot of, it’s books, and who wants those? But here’s the thing: the stove needs scrubbing, and the oven sometimes too. Whenever I look, the counters and sinks are crying out for bleach. Laundry ounts, mirrors streak: I need an arsenal of weapons to defend against dust, oil stains, odors, grime. Detergent, for one – a vaccuum, a dustpan, a broom, sponges and rags, a soap to remove spots, a spray to clean glass, a special cloth to polish jewelry and another to polish shoes. Francis, it’s a maddening game I play and almost always lose. You, on the other hand, had the sky for a house – trees a field, a cave. You owned the wind and the sun: your prize possessions were a song and a dream. These you have had to defend, never had to clean.

Does more stuff really make for a better life? Francis would certainly say quite the opposite became true for him.

Now, don’t get me wrong. The point of this sermon is not some counter-culture fist in the air about consumerism or achievement. Really, who am I to judge? Buy what you want in this season. And go after the achievements or the so-called successes of your dreams.

The real questions I want to raise today are the questions of liberation – the questions that Hosea’s prophecy about divine frustration and divine compassion provoke. I’m really looking for the invitations that Jesus the Liberator may be extending as well this Advent.

What if the economy and the culture we live in are in part crushing us? What if the peculiar idolatries of our time and place are choking us – leaving us stressed, disconnected, indebted, and alone?

What if Jesus has more freedom for us? What if Jesus could start to liberate us?

What’s the distance between our current experience of life, and the life we dream we are collectively meant for, the life that together we long for?

How might we start to walk away from one, and walk toward the other – to be on exodus with Jesus toward our own and our collective liberation.

Yvonne Abraham, a columnist in The Boston Globe, had a cool Thanksgiving piece up this week called: For this reformed shopaholic, a new take on Black Friday. She celebrated in this column a year of buying less, way less. And it was a bold and for me fun piece of journalism, because it wasn’t judgy at all. It was simply a story of her own liberation – of shifting her engagement with our consumer economy in a way that gained her freedom, and that also left her with a better impact on the people and environment of our world. It was her picture of walking away, making room for real joy, and participating in her liberation.

That’s where I got today’s Invitation to Whole Life Flourishing, which is this:

Invitations to Whole Life Flourishing

Buy less this month. Or choose particular days where you spend no money. Use some energy to do things that add freedom or joy to your life but cost nothing.

Unlike Abraham, for me this hasn’t been about shopping for more stuff. For me, this has meant other ways – rethinking, for instance, distractions on the internet that are supposedly free but cost my time and colonize my imagination – that don’t bring me joy or connection or freedom. Still, though, it’s a walking away from some of the habits and assumptions that aren’t serving. And this is the broader spiritual practice I’m inviting you to consider at the start of the Christmas season….

Spiritual Practice of the Week

Either daily or weekly, ask Jesus what you need to walk away from in order to make space for wonder, joy, and connection.

It’s my experience and my trust that as Jesus speaks to you, gives you direction, it will be for your personal and our collective liberation – to make more room for the great gifts of this season and the great gifts of God.